Acting on Impact

Share

As impact investing has grown in scale and maturity over the past ten years, it is increasingly demonstrating that investors can achieve positive social and environmental outcomes at the same time as generating strong returns.

Once a corner of the market more associated with non-profit philanthropy or development finance institutions, impact investing has come a long way in the past decade. Indeed, the impact investing industry, which aims to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return, has recently been estimated by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) to be worth just over €500bn globally. Given the scale of the market today, it’s not surprising that impact funds have caught the attention of many of the world’s leading investors in private equity. One of Europe’s largest pension investors, PGGM, which has €217bn under management, recently announced it was seeking exposure to impact private equity funds, for example.

Meanwhile a number of large, mainstream private equity fund managers have launched impact funds over the past few years. KKR launched a $1bn fundraising for a new impact fund in 2018, Bain Capital raised $390m for its Double Impact Fund in 2017 and is reported to be considering raising a second fund, TPG is currently raising its second impact fund, The Rise Fund II, which is targeting $3bn – significantly larger than its $2bn first Rise fund.

The involvement of these mega-players reflects not only institutional investor appetite for investments designed to help solve some of the world’s pressing social and environmental issues, but also attests to their belief that it is possible to achieve this while also generating market-rate returns. This belief has been proven. While a minority of investors seek below market-rate returns, 80% of private equity impact fund investors seek risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, according to a survey conducted by the GIIN. The same survey found that, as of 2018, investors reported an average realized gross return of 17% on equity since inception. In addition, investors are clearly satisfied with the results from their impact portfolios, with 97% saying impact performance had met or exceeded expectations, and 91% saying the same for financial performance.

These findings may surprise those who believe that impact investing implies a trade-off between generating positive social and environmental outcomes and financial returns. Yet the figures demonstrate that this view is unfounded. There is a clear recognition in the industry that its growth and ability to provide capital to address challenges such as poverty, hunger and inequality relies on offering investments that help investors meet their liabilities as well as their responsible investment objectives.

Unlike responsible investment (RI) and investing according to environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles, which tend to focus on doing no harm by identifying social or environmental risks that may hurt financial performance, impact investing is defined by the need to create positive externalities alongside financial returns. Examples include providing capital to develop clean energy or improving access to affordable healthcare and education in underserved populations.

Perhaps surprisingly, most of the capital raised by impact funds is targeted at developed markets, led by North America. However, funds targeting emerging markets, such as those in Africa, Latin America and Asia, are likely to achieve greatest impact because need is highest in these regions. Indeed, to be effective impact investing should be focused on the art of the possible, directing capital towards problems that are solvable, such as improving food security or financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa.

Phatisa, for example, is run by a deal team that has completed more than 250 deals in Africa and a portfolio team of 10 people that between them have more than 100 years of experience in Africa. The firm is investing in local food-related businesses with the potential to cut Africa’s food import bill from US$50bn-US$70bn a year, building greater food security in its markets.

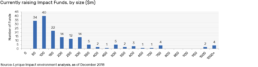

As the impact investing industry has grown, so has the diversity of investment options across both developed and emerging markets. Our analysis shows that there over 400 impact private equity fund managers and, of the 166 impact private equity funds currently raising capital, 67 offer a diversified strategy, with the remainder spread across sectors as diverse as infrastructure, food and agriculture, clean technology, financial services, healthcare and education.

Even specialist funds are creating diversified portfolios. Apis Partners, for example, targets financial services businesses in Africa and Asia (excluding China) and has provided funding for companies as diverse as an off-grid solar provider offering power to underserved communities, an online payments processor that enables card, mobile and other payments in East and Southern Africa and an Indian health insurance business. Meanwhile, Goodwell investments focuses on financial inclusion, fintech and inclusive growth.

This high level of variation is typical of a growing market and is beneficial for investors: a well-diversified portfolio of investments has the potential to offer the best risk-adjusted returns.

As with any investment, there are risks. The recent collapse of Abraaj Capital amid allegations of fraud and mismanagement has understandably led investors to be wary of emerging markets private equity. Impact investment, as with other types of investment, success requires a methodological approach. Fund manager selection in this space requires rigorous analysis of track record, future return generation potential and the capability to closely monitor the fund’s activities.

This is made more possible by the fact that the space today is similar to the broader private equity market around 30 years ago. There are growing numbers of smaller managers at a relatively early stage of developing their firms. This is positive – experienced investors in these funds have a role to play in supporting and nurturing rising stars. Indeed, the average size of impact funds remains relatively small, at $250m, according to our analysis of current fundraising.

Smaller funds face lower competition for assets at a time when the average private equity fund successfully reaching a close in the general (non-impact) market has risen two-fold in just five years to $1.3bn, according to Triago estimates.

Impact investing is clearly here to stay. There is demand from investors, which are increasingly facing pressure from a newer generation of stakeholders to use capital for societal as well as financial benefit, and an increasing supply of funds that are proving the sustainability and attractiveness of the impact model.